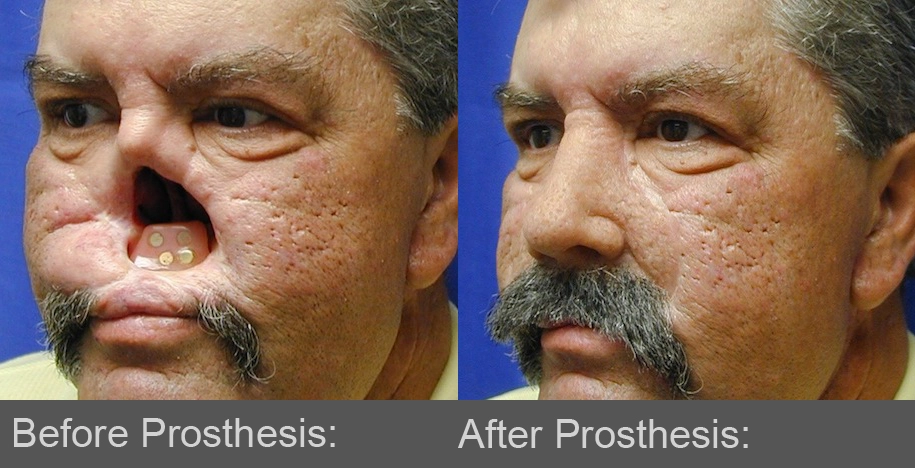

Life-changing transformation that was fatal for this man… Know more below…

One compelling example of an aesthetic object—though unconventional by traditional standards—is a facial prosthesis designed for reconstructive purposes following head and neck cancer surgery. When we typically think of “art,” prosthetic devices are rarely the first things that come to mind. However, there is no denying that these carefully crafted medical aids can be regarded as genuine works of art. They are not mass-produced items; instead, each one is uniquely tailored to the individual patient’s needs, features, and skin tone. The process of making such a prosthesis involves an extraordinary level of precision and craftsmanship—beginning with molding and sculpting the form to resemble the patient’s natural anatomy and followed by meticulous coloring and painting to achieve an almost invisible integration with the patient’s remaining facial features.

The impact of these prosthetic creations is not purely physical or medical; they have profound social and emotional effects as well. For patients who have undergone disfiguring surgeries, facial prostheses can restore not only form but a sense of normalcy, allowing them to engage in daily life without attracting unwanted attention or experiencing the psychological burden of stares, questions, or discrimination from others. This alone imbues these objects with an emotional and moral resonance far beyond what we expect from ordinary works of art.

In his framework for analyzing aesthetic items, philosopher Berys Gaut presents five key questions, or criteria, that help determine whether something should be considered a work of aesthetic value. The first of these questions is whether the work possesses moral beauty. In the case of prosthetic reconstruction, it is my strong belief that the work indeed embodies moral beauty. Unlike traditional artworks, which are often created to evoke admiration, pleasure, or emotional impact from an audience, the primary purpose of a prosthesis is to prevent a negative response. The creator does not aim to impress or provoke, but to provide the patient with dignity and comfort by concealing disfigurement that might otherwise result in public discomfort or stigma. The fact that, in many cases, observers don’t even realize they’re looking at a prosthetic is not a sign of failure, but of profound success. It reveals a moral commitment to compassion, empathy, and the reduction of human suffering, all of which enhance the aesthetic value of the work in ethical terms.

Gaut’s second question asks whether the work imparts knowledge to the viewer. In this regard, facial prostheses are again instructive. For those who take the time to examine or learn about the process behind their creation, the prosthetic becomes a vehicle for education. One can gain a deeper appreciation of human facial anatomy, skin tones, and the challenges posed by disfigurement and reconstruction. Furthermore, the work reveals the patience, dedication, and technical mastery required of the artists—or rather, the prosthetists—who design them. Their skill must extend beyond medical knowledge to include an artistic eye, precision, and a profound sensitivity to the emotional needs of their patients. This combination of science, art, and ethics enriches our understanding of both human resilience and artistic possibility.

The third criterion (which was skipped in the original structure) typically deals with whether the work exhibits technical excellence and innovation. In this case, facial prostheses are examples of how far technology and artistry have evolved to serve not just functional but also aesthetic and emotional needs. The use of modern materials, digital imaging, and advanced coloring techniques demonstrates innovation that enhances the overall impact of the work.

The fourth of Gaut’s questions is whether the response the work seeks to evoke is both morally appropriate and aesthetically pleasing. With facial prosthetics, the intended reaction is certainly ethical, and the visual outcome is indeed aesthetically positive. By restoring the symmetry and natural appearance of a patient’s face, these prostheses play a crucial role in enhancing self-esteem and reducing social alienation. They do not call attention to themselves, but rather help the individual blend in more comfortably, fostering inclusion instead of separation. In this sense, they succeed on both a moral and aesthetic level.

Lastly, Gaut poses the question of whether the artwork inspires the viewer to act in an ethically or morally better way. This is where the subtle but powerful influence of facial prosthetics becomes even more apparent. When people become aware that someone they see has undergone a life-altering procedure and is wearing a prosthesis, it can evoke empathy and challenge preconceived notions of beauty, normalcy, and health. These objects help to eliminate unconscious biases, such as the tendency to judge or avoid those with visible disfigurements. In doing so, they encourage a more compassionate, humane response—urging society to be more accepting, understanding, and respectful. That alone is a remarkable achievement for any form of art.

In conclusion, although facial prostheses might not traditionally be classified as “art” in the way paintings or sculptures are, they meet and even surpass many of the criteria for aesthetic evaluation. They are crafted with extraordinary skill and care, serve a deeply human purpose, communicate important knowledge, and elicit morally and emotionally valuable responses from those who encounter them. Through their transformative power—both physically and socially—these prostheses stand as true aesthetic achievements. They represent the intersection of art, science, compassion, and dignity, and remind us that beauty often lies not in what is seen, but in the love, purpose, and care that go into creation.